Face Masks and Social Distancing: How Identity Can Help or Hurt Change Efforts

In the early days of this pandemic that we are all living through, you must have questioned – as I did – the behavior of the throngs of people up and about in San Francisco, or of people in bars in other parts of the country, seemingly oblivious to the dangers of COVID-19. And three months later, as countries are opening up, we are continuing to see people on beaches and gathering places, maskless. Why are so many people ignoring health and safety guidelines?

Rafael (not his real name), an executive I was coaching, was typical of many very successful executives – ambitious, confident, competitive, but also charming. Unfortunately, he was someone who was reluctant to approach colleagues for feedback or for help. In the course of my interviews to gather 360-degree data about him, there were a couple of peers in his organization who I had spoken to who thought highly of Rafael and who were willing to help him. In my coaching sessions with Rafael, he agreed that reaching out to these two colleagues was a good idea. Yet he did not seem to take any steps to contact them. Over several coaching sessions, we finally figured out what the underlying issue was behind his reluctance: it was his belief that asking for feedback, especially from peers, was not consistent with his own image of himself. This would be showing vulnerability – not a desirable quality for executives like himself who needed to show their toughness and invincibility. His identity was about projecting himself as strong and powerful, and he associated asking for feedback with being wimpy or weak, and this was blocking his ability and willingness to change his behavior.

In reflecting on this executive and on recent events in the news, as well as reading a number of recent books on organizational and behavior change (see my list at the end), a number of lessons on effective behavior change have become clearer to me.

Let’s first take a look at one of these books, written by several McKinsey consultants (Feser et al.). The authors suggest that individuals will change their mindset and behavior if four elements are present: leaders are role-modeling the new behaviors; the individuals themselves understand what is being asked of them and this makes sense to them; they have the skills and opportunities to behave in the new way; and the structures, processes and systems support the changes they are being asked to make.

Many social scientists emphasize especially this last element. The situation or our environment has a greater influence on our behavior that we might believe, and that by aligning structures, processes and systems with the desired behavior outcomes, organizational change is more likely to be successful. A similar point has been made by Thaler and Sunstein in their concept of “nudges,” which are attempts to influence our behavior with small suggestions and positive reinforcement (e.g., product placements, default options – “Would you like fries with that?”). Nudges have been applied successfully by organizations both with employees in the workplace and with consumers in the marketplace.

However, what’s seems missing in these approaches is the role of identity and the importance of developing habits for actually changing behavior more permanently. In his recent book, James Clear says that “true behavior change is identity change.” What does he mean by this? He writes, “Your behaviors are usually a reflection of your identity. What you do is an indication of the type of person you believe that you are – either consciously or nonconsciously,” and “the more deeply a thought or action is tied to your identity, the more difficult it is to change it.” Indeed, “Becoming the best version of yourself requires you to continuously edit your beliefs and to upgrade and expand your identity.”

In their book, Switch, the Heaths make a similar point. Using an identity framework, they point out that we ask ourselves three questions before making a decision on whether or not to change our behavior: Who am I? What kind of situation is this? What would someone like me do in this situation? This explains in part why people today still insist on going on with their routines despite the dangers of COVID-19. Those who consider themselves as young, healthy and hedonistic (“I never get sick,” “I love having a good time”) will not believe that the situation warrants their having to stay home (“It’s not that bad,” “I’ve been cooped up for too long”). Besides, many of their friends are no longer staying home anyway (“Let’s go and grab a drink; it wouldn’t hurt to have a bit of fun these days,” “You can’t stay at home forever, especially now that the weather is getting better”). And for others, it’s about their identity as individualistic Americans (“Other people who are like me would never think about wearing a mask,” “I don’t like anyone, especially the government, telling me what to do – that’s unAmerican”).

So how do you change your identity? According to Clear, through a two-step process: first, decide on the type of person you want to be, and second, prove it to yourself with small wins. To paraphrase Clear, you start by clarifying your identity and not by focusing on results or outcomes: “The focus should always be in becoming that type of person, not getting a particular outcome.” However, this is not sufficient, in my experience. You also need to consider how you can think about your identity differently, or about your different identities and which will best help you achieve your goals.

Recently, one of my students, who had just started working for a museum, described the frustrations she was feeling as a result of the resistance to change among some of the staff in the museum. If you’ve been going to museums in the past decade, I’m sure you have noticed all the changes that have been implemented to make museums more user-friendly, such as with more interactive and hands-on exhibits. In this museum, however, a number of long-tenured employees had been resisting any changes to modernize their museum. For this “old guard,” museums were about preserving the art and making sure museum-goers did not get too close to these objects for fear of damaging them; they saw themselves as guardians of the art. Asking these employees to change the way the museum presented its pieces was going against their deeply ingrained beliefs and identity.

So here are three recommendations for change leaders and for anyone interested in better understanding the dynamics of behavior change. First, and perhaps the most important, is role modeling. If you are a leader, you need to walk the talk and practice what you preach. You need to show others that you are living proof of applying the lessons you want others to learn.

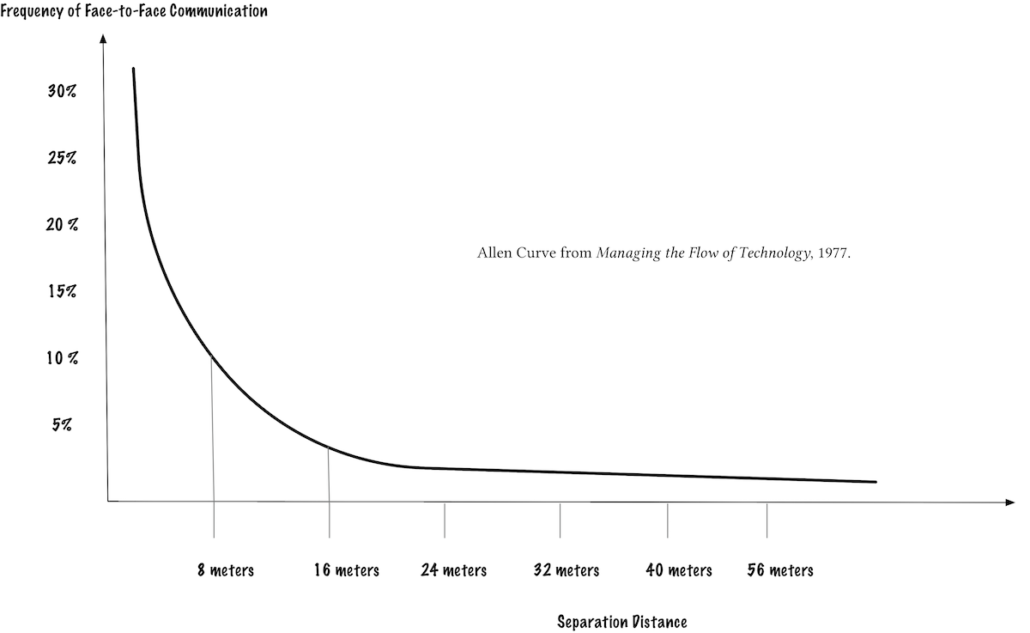

Second, make sure that the environment or the organization’s structures, systems and processes are aligned with the goals of the change. This is where nudges can come into play. Companies like Apple and Google, for example, have cafeterias with long tables where employees from different departments can sit together (although perhaps with more social distancing these days) – therefore reinforcing the importance of collaboration.

And third, make sure that you understand people’s identity and how their identity can be made congruent with the changes they are being asked to make. In the case of the museum, this might mean re-framing the old guard’s identity and recasting their role a bit differently. Remember that all of us have more than one identity and are capable of expanding our identities. For example, the museum director could start redefining the museum employees’ role as one that strives to maximize the museum-goer’s experience while at the museum. He could then ask some of these old-guard employees to join other employees on a task force to identify new ways to enhance this experience to make sure they continue to showcase the art. He could encourage them to learn some of the new technologies (e.g., having personalized recommendations for visitors based on data that would be collected beforehand, creating more immersive digital experiences) by contacting their counterparts in other museums and finding out about best practices. This re-framing gets away from having to reject one’s identity completely, a difficult step for many of us.

In Rafael’s case, over time and after many coaching sessions, he began to view his identity a bit differently: that an effective executive is one who actively seeks feedback. By my pointing to him several effective executives in his organization who modeled this behavior, Rafael was able to reframe his idealized image of a successful executive. It has not been easy; through some initial small wins (for example, he has reached out to have coffee with several peers and found the conversations to be very helpful), I am hoping he will continue to make the changes he needs to make to be successful.

And for those who are still ignoring the warnings to socially distance themselves, consider reframing your identity or expanding your identity. Yes, you are a healthy person who does not get sick but will make an exception and practice social distancing this time around just in case, since getting the virus is not going to be fun, to say the least. Yes, you are an individualistic American, but nonetheless an American who considers the rights and benefits of others (just like wearing seat belts or not smoking indoors does not necessarily trample on your individual rights). And being American also someone who cares about your family, friends and others and wants to make sure you are helping to make a positive difference. And yes, if some of the people you admire and respect (including public figures and celebrities), as well as some of your friends, are socially distancing and wearing masks (admittedly, a big “if” in some cases), perhaps you can too.

References:

Clear, J. (2018), Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. New York: Avery.

Feser, C. et al. (2018). Leadership at Scale: Better Leadership, Better Results. London: Nicholas Brealey.

Goldsmith M. and Reiter, M. (2015). Triggers: Creating Behavior That Lasts – Becoming the Person You Want to Be. New York: Crown.

Heath, C. and Heath, D. (2010). Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. New York: Currency.

Kotter, J. (1995). Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Harvard Business Review.

Thaler, R. and Sunstein, C. (2009). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. New York: Penguin Books.