Johan de Nysschen (previously the successful head of Audi of

America) was appointed to lead the Cadillac division of General Motors in 2014.

When he joined GM, one of his first decisions was to place physical and

psychological distance between Cadillac and Detroit, moving Cadillac’s

headquarters from Motown to Manhattan in 2015. In New York, Mr. de Nysschen

felt that Cadillac could attract top talent, follow consumer trends more

closely, and gain new buyers.

Unfortunately, Cadillac, a brand that had begun to transform its outdated image, continues to struggle. Its sales plunged to 156,000 in 2017 (from 180,000 in 2013) while other competitors have become more successful. There are many reasons for his lack of success. Robert Lutz, a former Chrysler and BMW executive, has suggested that de Nysschen’s physical separation from Detroit made it harder to influence others (Ulrich, 2018). During his tenure at GM, Lutz recalled being able to march into a finance executive’s office if he had removed $200 worth of chrome that Mr. Lutz viewed as critical. “I’d say, ‘Where did the chrome go?” Mr. Lutz said. “You stare him in the eye, argue with him and get it fixed. Even in this day of electronic connectedness, distance matters.”

Based on my own experience as a global manager for many years as well as the hundreds of interviews I have conducted with global managers, social distance –the gap in the degree of emotional connection between individuals as well as among team members – is a key variable in the success of global managers and global teams. For example, quite a few expats I have met over the years have suffered from the “out of sight, out of mind” syndrome when they start to lose touch with their mentors or senior executives back in the home office.

Overcoming the disadvantages of distance in general is one of the key challenges facing global companies today. Multinationals expand overseas for compelling business reasons

- To seek new markets for their products and services.

- To take advantage of countries’ resources (what the economists call factor endowments) as well as its human capital, such as an educated workforce or particular skill sets in that country.

- To seek efficiencies.

At the same time, there is no doubt that distance makes it more difficult for multinationals to manage their subsidiaries and overseas locations. Youssef and Luthans (2012) have pointed out that global leaders these days experience three types of distance:

- physical distance (due to geographical dispersion),

- structural distance (due to organizational factors like decentralization and span of control),

- psychological or social distance (due to status or power differentials).

Specifically, social

distance reduces global managers’ ability to network, their effectiveness in

building trust, and their efficiency in getting the work done. Communication

gets misconstrued, and it is much harder to influence others when you cannot

see your counterparts’ non-verbals. It is also harder to get feedback and to

learn from the other party. To reduce the social distance gap, it is important

to recognize and address what I consider to be its five major barriers.

First,

Barrier is geography or physical distance.

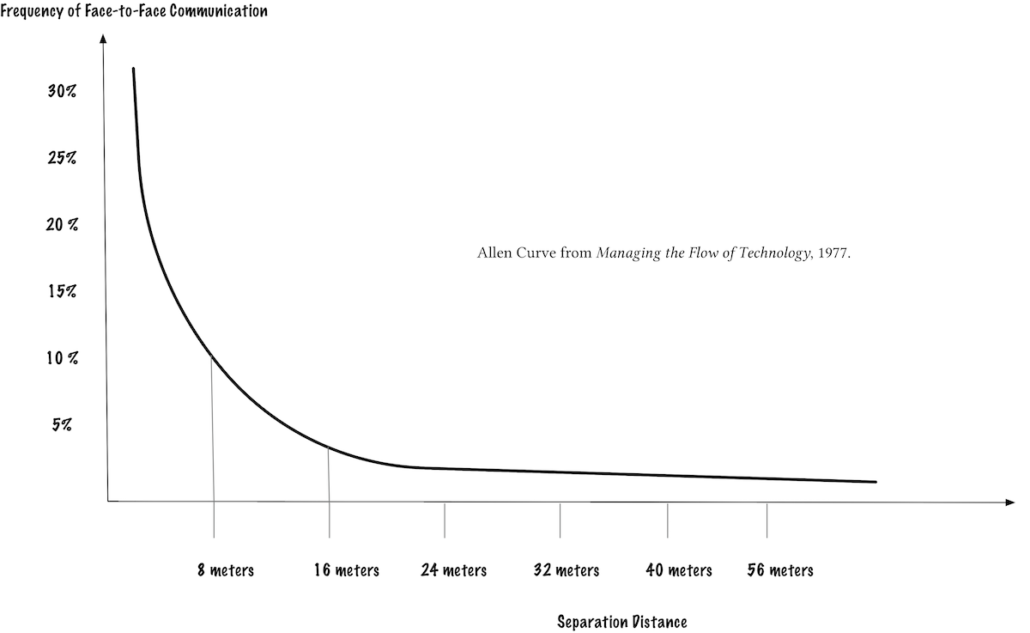

As Epley (2014) has pointed out, physical distance is an important aspect of our engagement with others. He cites evidence from war and battles that soldiers who are fighting are more reluctant to use their weapons when the enemy is close to them physically. MIT professor Thomas Allen created his Allen curve, which shows the relationship between frequency of interaction and physical distance:

Second,

Strive for face-to-face interactions with your team and with other stakeholders, when feasible.

“The most successful leaders make sure they establish personal connections.” As Betsy Myers (2011) has pointed out in her book, making connections is one of the qualities of effective leaders. Managing by walking around (or MBWA), popularized by Tom Peters, is still a fundamentally sound practice. When Apple was designing its new headquarters (a circular structure with 12,000 employees), its executives made it a point to make sure that the physical layout of the building maximized face-to-face contacts among employees across functions. This design was heavily influenced by the late Steve Jobs, who believed firmly in manipulating space to influence behavior. Zappos founder Tony Hsieh has talked about encouraging “collisions;” in fact, in its headquarters office, he has closed all side entrances so that all associates have to go through one main door.

Third,

Barrier is national culture.

Even though globalization and the popularity of branded products universally may seem like national cultures are becoming less important, virtually all the successful global managers I have interviewed recognize how important it is to be aware of national cultural values and norms when managing workers in different countries.

My suggestion for global managers: Develop your cultural competency by learning the cultural norms of the countries where your team members and other stakeholders are from.

Carlos Ghosn, who led a successful turnaround of Nissan in Japan, has suggested that it was important for him to like the Japanese culture and show genuine curiosity about it.

Fourth,

Barrier is language.

Yes, English seems to be the language of business these days, with 1.75 billion people on the planet speaking English at a useful level, and for many organizations (including organizations with roots in non-English-speaking countries such as Unilever and BMW), English is commonly spoken in their offices. In fact, when bringing together stakeholders such as customers, vendors, or managers from different parts of the world, English seems to be the default language used by these corporations. Many companies in Japan require candidates for manager positions to achieve a certain level of proficiency in an English exam before they are even considered.

However, not being able to speak the local language can be a barrier to reducing social distance. There are still many parts of the world where English is not spoken in the work place, or where employees, not feeling confident in their ability to speak English, may hesitate to express their opinions. Quite a few global managers hire a local translator, or rely on their local administrative assistant, for help in translation and interpretation. But these only go so far and certainly require quite a bit of effort.

My suggestion for global managers:

- Take language lessons, or at least learn a few words in the local language.

- In parallel, be aware of assuming that a lack of fluency in English among your local staff means a low level of competency.

- Not only will learning a few words in the local language help you communicate better with your local team, but will also send a signal that you are interested in their culture, and that you are going out of your way to show that you want to connect with them on more than just a business level.

Fifth,

Barrier is around structure, status and hierarchy.

Research studies have documented how upward communication is easily squelched by high-power and high-status individuals in organizations. A recent example (one among many) is the emissions scandal at Volkswagen, in which “… experts and company insiders draw a direct connection between the scandal and Volkswagen’s rigid culture, in which mid-level managers and low-level workers were reluctant to question their superiors’ decisions, including the decision to cheat on emission tests.” (This is from a story about the VW scandal by Vivienne Walt published in the August 2018 issue of Fortune magazine). Hierarchy will always be present in large global companies and as much as some organizations have tried to flatten their structures, it will never go away.

Furthermore, there are some cultures where “power distance” is valued, and where undue respect and deference is given to those in authority.

In your interactions, make sure you do more of the following:

- Ask for input and feedback, actively listen, acknowledge your ignorance.

- Be accessible and visible.

- Make sure you do less of the following: punish employees for speaking up especially when it is about bad news, give orders unilaterally,

- Refuse to admit when you have made a mistake.

Sixth,

Barrier is identity.

Many research studies have shown that individuals categorize themselves into different group memberships (e.g., race, gender, profession, function, nationality) and once they define themselves into these memberships, two things happen: they will tend to like those who they feel are “like” them in some way; and they will start to define those who are in their “out-group” and like them less. The stronger their identification with these categories or memberships, the more intense these things happen. However, even when categories seem trivial, such as a shared birthday – what psychologists term as “mere belonging” – a sense of connectedness begins to form quickly. This is because we are hard-wired to form and maintain social bonds. Neuroscience has shown that the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) is a spot on each side of our brain that helps our memory and decision-making; different parts of it get activated when we are making judgments about ourselves versus others. When others are those we consider to be distant from us, those parts of our MPFC do not get activated as much, and so we don’t think of others as compassionately as we might otherwise think of those who are closer to us.

Global managers who deal with virtual teams sometimes struggle with finding a sense of identity and cohesiveness for their teams.

Establish a sense of community and shared purpose with your teams and other stakeholders by:

- Aligning the team’s goals with the larger organizational goals,

- Inspiring your team to have meaningful and challenging goals,

- Finding bases for team membership that reinforce a shared sense of similarity and identity.

- In addition, global managers should not neglect the basics of managing virtual teams effectively, for example:

- Scheduling regular one-on-one conversations with team members, establishing regular times and routines for your meetings;

- Regularly sending updates and communicating information and interesting pieces of news (e.g., executives who may need a bit more convincing about the value of the work that the team is doing, or even rumors on changes in the home office) so that the team feels connected.

Even though your team might be virtual, there are ways you can get members to get to know each other a little bit better and find some commonalities among them by, for example, setting up a virtual happy hour via Google Hangouts or a shared hashtag for Twitter (as suggested by PJ Camp Malik), or even build some time at the end of virtual meetings for non-work-related conversations (e.g., sports, music).

Epley,

N. (2014). Mindwise: How We Understand

What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want. New York: Knopf Books.

Myers,

B. (2011). Take the Lead: Motivate,

Inspire, and Bring Out the Best in Yourself and Everyone Around You. New

York: Atria Books.

Ulrich,

L. Cadillac Makes Great Cars. Too Bad Americans Want SUVs. New York Times, May 17, 2018.

Youseff,

C. and Luthans, F. (2012). Positive Global Leadership. Journal of World Business, 47 (4): 539-547.